Descriere

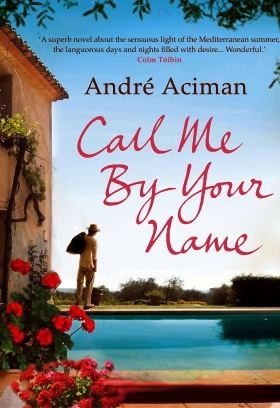

Download Call me by your name by Andre Aciman book english .PDF (ebook) Andr Aciman, hailed as a writer of "fiction at its most supremely interesting" (The New York Review of Books), has written a novel that charts the life of a man named Paul, whose loves remain as consuming and as covetous throughout his adulthood as they were in his adolescence. Whether the setting is southern Italy, where as a boy he has a crush on his parents' cabinetmaker, or a snowbound campus in New England, where his enduring passion for a girl he'll meet again and again over the years is punctuated by anonymous encounters with men; whether he's on a tennis court in Central Park, or on a New York sidewalk in early spring, his attachments are ungraspable, transient, and forever underwritten by raw desire--not for just one person's body but, inevitably, for someone else's as well. In Enigma Variations, Aciman maps the most inscrutable corners of passion, proving to be an unsparing reader of the human psyche and a master stylist. With language at once lyrical, bare-knuckled, and unabashedly candid, he casts a sensuous, shimmering light over each facet of desire to probe how we ache, want, and waver, and ultimately how we sometimes falter and let go of those who may want to offer only what we crave from them. Ahead of every step Paul takes, his hopes, denials, fears, and regrets are always ready to lay their traps. Yet the dream of love lingers. We may not always know what we want. We may remain enigmas to ourselves and to others. But sooner or later we discover who we've always known we were. Prolog “Later!” The word, the voice, the attitude. I’d never heard anyone use “later” to say goodbye before. It sounded harsh, curt, and dismissive, spoken with the veiled indifference of people who may not care to see or hear from you again. It is the first thing I remember about him, and I can hear it still today. Later! I shut my eyes, say the word, and I’m back in Italy, so many years ago, walking down the tree-lined driveway, watching him step out of the cab, billowy blue shirt, wide-open collar, sunglasses, straw hat, skin everywhere. Suddenly he’s shaking my hand, handing me his backpack, removing his suitcase from the trunk of the cab, asking if my father is home. It might have started right there and then: the shirt, the rolled-up sleeves, the rounded balls of his heels slipping in and out of his frayed espadrilles, eager to test the hot gravel path that led to our house, every stride already asking, Which way to the beach? This summer’s houseguest. Another bore. Then, almost without thinking, and with his back already turned to the car, he waves the back of his free hand and utters a careless Later! to another passenger in the car who has probably split the fare from the station. No name added, no jest to smooth out the ruffled leave-taking, nothing. His one-word send-off: brisk, bold, and blunted—take your pick, he couldn’t be bothered which. You watch, I thought, this is how he’ll say goodbye to us when the time comes. With a gruff, slapdash Later! Meanwhile, we’d have to put up with him for six long weeks. I was thoroughly intimidated. The unapproachable sort. I could grow to like him, though. From rounded chin to rounded heel. Then, within days, I would learn to hate him. This, the very person whose photo on the application form months earlier had leapt out with promises of instant affinities. Taking in summer guests was my parents’ way of helping young academics revise a manuscript before publication. For six weeks each summer I’d have to vacate my bedroom and move one room down the corridor into a much smaller room that had once belonged to my grandfather. During the winter months, when we were away in the city, it became a part-time toolshed, storage room, and attic where rumor had it my grandfather, my namesake, still ground his teeth in his eternal sleep. Summer residents didn’t have to pay anything, were given the full run of the house, and could basically do anything they pleased, provided they spent an hour or so a day helping my father with his correspondence and assorted paperwork. They became part of the family, and after about fifteen years of doing this, we had gotten used to a shower of postcards and gift packages not only around Christmastime but all year long from people who were now totally devoted to our family and would go out of their way when they were in Europe to drop by B. for a day or two with their family and take a nostalgic tour of their old digs. At meals there were frequently two or three other guests, sometimes neighbors or relatives, sometimes colleagues, lawyers, doctors, the rich and famous who’d drop by to see my father on their way to their own summer houses. Sometimes we’d even open our dining room to the occasional tourist couple who’d heard of the old villa and simply wanted to come by and take a peek and were totally enchanted when asked to eat with us and tell us all about themselves, while Mafalda, informed at the last minute, dished out her usual fare. My father, who was reserved and shy in private, loved nothing better than to have some precocious rising expert in a field keep the conversation going in a few languages while the hot summer sun, after a few glasses of rosatello, ushered in the unavoidable afternoon torpor. We named the task dinner drudgery —and, after a while, so did most of our six-week guests.